|

DAVID PIZZANELLI Born London, England |

Work shown in the exhibition:

ARABESQUE

1989

Mirror-backed achromate white light transmission hologram

10" x 8".

Silver halide on glass.

MOTHER AND CHILD

1989

Mirror-backed achromate white light transmission hologram.

4" x 5".

Silver halide on glass.

Edition # 4/25

GOOD MORNING

1989

Mirror-backed achromate white light transmission hologram.

IO" x 8"".Silver halide on glass

View an illustrated list of works by

David Pizzanelli in the Jonathan Ross Hologram Collection.

.

|

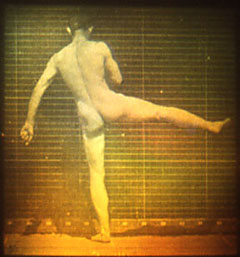

THE MUYBRIDGE ANIMATIONS SERIES Eadweard Muybridge was born at Kingston-upon-Thames in April 1830. As a young man he sailed to America to seek his fortune and settled in San Francisco. By the late 1860s he had established a reputation as a first rate landscape photographer and a prodigious inventor. Today, however, Muybridge is chiefly remembered for his extraordinary work with the photography of movement. My own interest in Muybridge's work began in 1987 when, examining the photographs from Animal Locomotion, I was amazed to discover that I could see the images in 3D. A few months earlier I had joined the Stereoscopic Society in London and had learned the technique of "free-viewing": the direct viewing of stereoscopic photographs without the aid of a stereoscope or viewer. |

ARABESQUE 1989 ARABESQUE 1989 |

|

Normally when we look at a photograph both our eyes converge to examine a detail of interest. When looking at a pair of stereoscopic photographs each eye is directed at the appropriate image examining the same detail of the scene, but from two view points which the brain combines to form a three-dimensional mental image. This technique has recently come back into vogue with the sudden popularity of random-dot stereograms. Free-viewing on to the Muybridge Photographs revealed that consecutive prints in the sequences were stereoscopic, producing clearly three-dimensional images. None of the many books written about the Muybridge photographs make any mention of the fact that they are stereoscopic sequences, nor did Muybridge himself consider that this was of any importance, although he was himself a skilled stereophotographer. The fact that the sequences have parallax information in them is a direct result of the way in which the photographs were taken: Muybridge was working several years before the invention of the cine camera, so in order to expose his photographic plates in quick succession he designed a method by which a number of individual cameras were triggered by the subjects passing in front of each camera in turn. Because the cameras were arranged in a line a few inches apart from each other, they recorded different perspective views of the subject. This provided me with a wonderful opportunity: because all the individual images related collectively as a stereoscopic sequence they could be brought together in a hologram and synthesized into a single three-dimensional, animated scene which would show all the spatial depth of the original event as it took place, a century before. A total of 20 holograms were made of selected Muybridge sequences. Each one was chosen because it illustrated a different aspect of stereoscopic and temporal parallax (the subject of my Ph.D), however they were also chosen because of the images. The appropriated photographs are transformed in the holograms not simply because they are now three dimensional animations but because we view them with 20th Century eyes and see afresh just how extraordinary some of the images are. When they were made, the sobriety of the scientific undertaking exculpated the nudity, as works of art they are similarly absolved, but in this context we are enticed to pause and ponder what they signify. The holograms are just a conduit for the puissance which is dormant in the photographs, just as the parallax was latent, waiting to be discovered. |

|

Information on this page has been taken from the catalogue: 3 x 8 + 1, 25 Holographic Artworks from the Jonathan Ross Collection.

|